(7 Minutes)

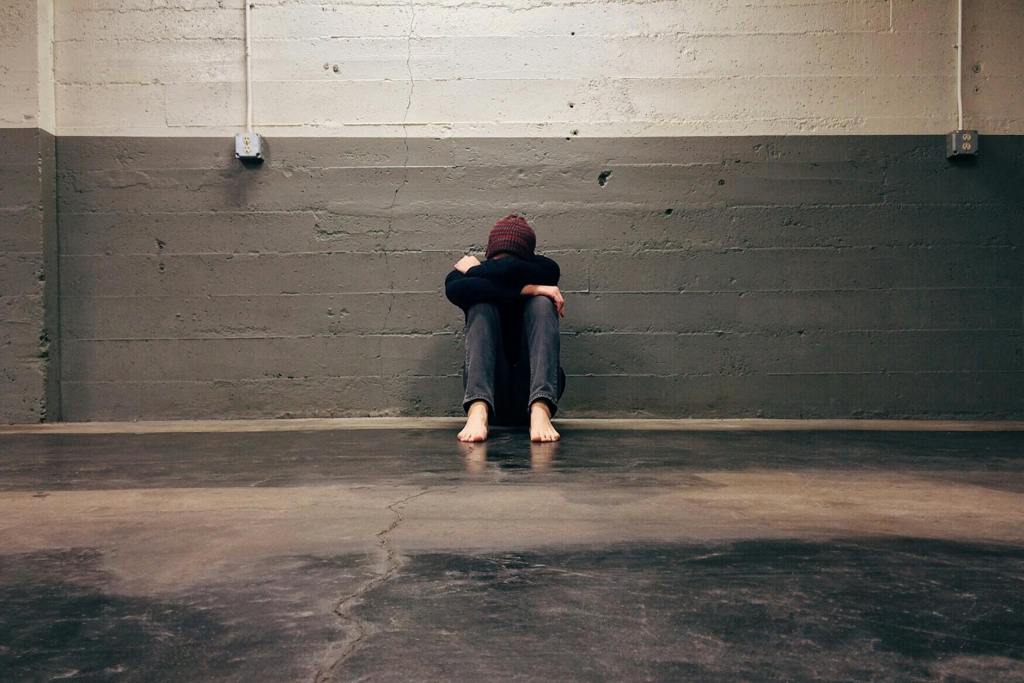

When Struggle Becomes Our Greatest Teacher

There’s a story I keep coming back to whenever I think about learning and growth. It’s about a conversation between a therapist and her client who was going through a particularly difficult divorce. The client, exhausted from months of emotional turmoil, asked desperately, “When will this pain serve a purpose? When will I finally learn something from all this suffering?”

The therapist paused thoughtfully before responding, “You’re learning right now. You’re learning things about yourself, about relationships, about resilience that you could never have discovered while everything was comfortable. The question isn’t whether pain teaches us—it’s whether we’re willing to be students of our own discomfort.”

That exchange has stayed with me because it captures something we all know but rarely want to acknowledge: our most profound learning often emerges from our most difficult experiences. While comfort feels good and pain feels terrible, there’s mounting evidence—both scientific and anecdotal—that suggests struggle might be one of our most effective teachers.

The Science of Struggle

Neuroscientists have discovered something fascinating about how our brains respond to challenge versus comfort. When we’re in familiar, comfortable situations, our brains operate in what researchers call “default mode”—essentially autopilot. Neural pathways that are already well-established handle routine tasks efficiently, but very little new learning occurs.

Pain and struggle, however, trigger what neuroscientists call “neuroplasticity”—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections. When we encounter difficult or unfamiliar situations, our brains are forced to create new pathways, to adapt, to literally rewire themselves to cope with the challenge.

Dr. Norman Doidge, a psychiatrist and researcher who wrote extensively about brain plasticity, found that the brain changes most dramatically when it’s pushed beyond its comfort zone. Mild stress and manageable challenges stimulate the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that essentially acts like fertilizer for brain cells, promoting new growth and stronger connections.

But here’s where it gets interesting: the brain doesn’t just adapt to handle the specific challenge at hand. The neural flexibility developed through overcoming one difficulty transfers to other areas of life. People who have successfully navigated significant challenges often show enhanced problem-solving abilities, greater emotional regulation, and improved resilience across multiple domains.

This isn’t just theoretical. Studies of people who have experienced what psychologists call “post-traumatic growth”—positive psychological change following adversity—show measurable changes in brain structure. The areas responsible for emotional regulation, empathy, and cognitive flexibility literally grow larger and more interconnected.

The Comfort Zone Paradox

I’ve been thinking about my own experiences with learning, and I can trace most of my significant growth to periods of discomfort. The job that felt too challenging and left me questioning my abilities every day taught me more about my capabilities than years of easy assignments. The relationship that ended painfully revealed patterns I’d been blind to for years. The financial struggles that kept me awake at night forced me to develop resourcefulness I didn’t know I possessed.

Comfort, by contrast, feels good but teaches us relatively little. When life is going smoothly, when our routines are working, when we’re not being challenged, we tend to coast. We rely on existing skills and knowledge rather than developing new ones. We become, in a sense, experts at our current level of functioning but don’t push beyond it.

This creates what researchers call the “comfort zone paradox.” The very thing that makes us feel safe and secure—familiar patterns, predictable outcomes, manageable challenges—also limits our potential for growth. Comfort preserves our current state but rarely elevates it.

I notice this in my own life when I compare periods of ease with periods of struggle. During comfortable times, I maintain my existing habits and skills, but I don’t typically develop new ones. I’m happier day-to-day, but I’m not necessarily growing or learning at the same rate.

The Oprah Winfrey Example

Consider the life trajectory of Oprah Winfrey, whose story illustrates this principle on a grand scale. Born into poverty in rural Mississippi, Winfrey faced challenges that would have broken many people: childhood abuse, teenage pregnancy, racial discrimination, and professional setbacks that could have ended her career before it began.

Yet each of these painful experiences seemed to contribute to her eventual success in ways that comfort never could have. Her personal struggles with weight and self-image made her a more empathetic interviewer. Her experience with trauma helped her connect with guests and audiences dealing with their own pain. Her encounters with discrimination gave her a unique perspective on social issues that resonated with millions.

In interviews, Winfrey often speaks about how her most difficult experiences taught her the most valuable lessons. She credits her painful childhood with developing her empathy, her professional setbacks with teaching her resilience, and her personal struggles with giving her authenticity that audiences could sense and trust.

“The greatest discovery of all time is that a person can change his future by merely changing his attitude,” she once said. But that attitude, that wisdom, that ability to transform pain into purpose—these weren’t lessons she could have learned from a comfortable life. They were forged in the fire of real struggle.

This isn’t to romanticize suffering or suggest that trauma is somehow good for us. Rather, it’s to acknowledge that when difficult experiences are inevitable—and they are—we have a choice about how we engage with them. We can resist the lessons they offer, or we can allow them to teach us things we couldn’t learn any other way.

The Difference Between Suffering and Learning

I want to be careful here because there’s an important distinction between suffering that leads to growth and suffering that simply breaks us down. Not all pain is instructive. Not all struggle leads to wisdom. The difference seems to lie in how we engage with our difficult experiences.

Researchers have identified several factors that determine whether painful experiences become learning opportunities or simply sources of ongoing trauma. The presence of support systems, the ability to make meaning from suffering, the development of coping strategies, and the maintenance of hope for the future all play crucial roles.

Viktor Frankl, the psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, wrote about this distinction in his profound book “Man’s Search for Meaning.” He observed that even in the most extreme circumstances, some people found ways to grow and learn from their suffering while others were simply crushed by it. The difference wasn’t in the severity of their experiences but in their ability to find meaning and purpose in their pain.

This suggests that the learning potential of painful experiences isn’t automatic—it requires active engagement, reflection, and often the support of others. Pain by itself doesn’t teach us anything. It’s our response to pain, our willingness to examine what it reveals about ourselves and our world, that transforms suffering into wisdom.

The Uncomfortable Comfort of Discomfort

I’ve started paying attention to my own relationship with discomfort, and I’ve noticed something interesting. The challenges that initially felt overwhelming often become, in retrospect, the experiences I’m most grateful for. The job that stressed me out daily taught me skills I use constantly. The relationship that ended painfully helped me understand myself in ways I never had before.

This has led me to develop what I can only describe as an “uncomfortable comfort” with discomfort. I still don’t enjoy difficult experiences while I’m in them, but I’ve developed a kind of faith in their eventual value. I’ve learned to recognize the signs of growth even when they’re wrapped in the clothing of stress, uncertainty, or pain.

This doesn’t mean I seek out suffering or believe that all pain is good. But it does mean I’ve stopped seeing discomfort as something to be avoided at all costs. Instead, I try to approach difficult experiences with curiosity: What might this teach me? How might this change me? What skills might I develop by navigating this challenge?

The Biological Imperative

From an evolutionary perspective, this makes perfect sense. Our ancestors who learned quickly from painful experiences—who could adapt their behavior after touching a hot surface or encountering a dangerous animal—were more likely to survive and reproduce. Those who remained comfortable in familiar patterns, unable to adapt when circumstances changed, were less likely to pass on their genes.

This learning-through-discomfort mechanism is built into our biology. The stress response that feels so unpleasant actually serves multiple functions: it focuses our attention, enhances our memory formation, and motivates us to develop new strategies for dealing with challenges.

Research has shown that moderate levels of stress actually improve learning and memory. Students who experience mild anxiety before an exam often perform better than those who feel completely relaxed. Athletes who feel pre-competition nerves frequently have better performances than those who feel no pressure at all.

The key word here is “moderate.” Too little stress and we don’t learn effectively; too much stress and we become overwhelmed and unable to process information. The optimal learning zone seems to exist in that uncomfortable middle ground where we’re challenged but not overwhelmed, stressed but not paralyzed.

The Modern Comfort Crisis

I’ve been thinking about how this principle applies to our current cultural moment. We live in a time when comfort is more available than ever before. We have technologies that eliminate many daily inconveniences, entertainment that can distract us from any discomfort, and a culture that often treats any form of struggle as a problem to be solved rather than an experience to be learned from.

While these comforts are wonderful in many ways, I wonder if they might also be limiting our growth. If we can avoid most forms of discomfort, do we also avoid the learning that comes from navigating difficulty? If we can instantly gratify most desires, do we miss out on the resilience that comes from delayed gratification and frustrated expectations?

I see this in my own life when I notice how much I rely on external comforts to regulate my emotional state. When I’m stressed, I reach for my phone. When I’m bored, I find entertainment. When I’m uncomfortable, I look for ways to make myself feel better immediately.

There’s nothing wrong with seeking comfort, but I wonder what I might be missing by not sitting with discomfort long enough to learn from it. What insights might emerge if I spent more time in that uncomfortable space where real learning happens?

The Art of Productive Struggle

Perhaps the key is learning to distinguish between productive struggle and unnecessary suffering. Not all discomfort is created equal. Some challenges push us to grow in valuable ways, while others simply drain our energy without offering meaningful lessons.

Productive struggle seems to have certain characteristics: it’s challenging but not overwhelming, it’s temporary rather than endless, it’s connected to our values and goals, and it occurs within a supportive context. This kind of struggle stretches us without breaking us, teaches us without traumatizing us.

I think about the difference between the discomfort of learning a new skill and the discomfort of being in a toxic relationship. Both are painful, but one leads to growth and capability while the other leads to diminishment and trauma. The challenge is learning to recognize which is which.

Embracing the Paradox

The relationship between pain and learning presents us with a fundamental paradox: the experiences that feel worst often teach us the most, while the experiences that feel best often teach us the least. This isn’t a cruel cosmic joke—it’s a feature of how learning works.

Growth requires us to move beyond our current capabilities, to venture into unfamiliar territory, to risk failure and disappointment. This process inevitably involves discomfort because we’re literally rewiring our brains, challenging our assumptions, and expanding our capacity to handle complexity.

Comfort, by contrast, signals to our brain that we’re in a safe, familiar environment where existing patterns and responses are adequate. There’s no need to develop new capabilities or perspectives because current ones are working fine.

This doesn’t mean we should seek out pain or avoid comfort entirely. Rather, it suggests that we might benefit from reframing our relationship with discomfort. Instead of seeing it as something to be avoided, we might learn to recognize it as a signal that we’re in a learning zone.

The Invitation of Discomfort

I’ve come to think of discomfort as an invitation—an invitation to grow, to learn, to become more than we currently are. It’s an invitation we can accept or decline, but it’s always there, waiting for us to respond.

When I’m facing a difficult situation now, I try to ask myself: What is this experience inviting me to learn? What capabilities might I develop by navigating this challenge? How might I be different on the other side of this struggle?

These questions don’t make the discomfort go away, but they help me engage with it more purposefully. They transform pain from something that happens to me into something I can work with, learn from, and eventually integrate into my understanding of myself and the world.

The uncomfortable truth is that our most profound learning often comes through our most difficult experiences. Not because pain is inherently good, but because navigating difficulty requires us to develop new capabilities, perspectives, and resilience. Comfort maintains our current state; discomfort elevates it.

This doesn’t mean we should seek out suffering or avoid all comfort. But it does suggest that when difficult experiences are inevitable—and they are—we have a choice about how we engage with them. We can resist the lessons they offer, or we can allow them to teach us things we couldn’t learn any other way.

Perhaps the goal isn’t to eliminate discomfort from our lives, but to develop the wisdom to know when it’s serving us and the courage to stay present with it long enough to receive its gifts. In a world that often promises easy solutions and instant gratification, this might be one of the most valuable skills we can develop: the ability to learn from our pain without being defeated by it.

The science is clear, the examples are abundant, and our own experiences confirm it: we learn more through pain than comfort. The question isn’t whether this is true, but whether we’re willing to be students of our own discomfort, to find meaning in our struggles, and to allow our most difficult experiences to become our most profound teachers.

Leave a comment